How Fiction Strengthens Human Truth

My Favorite Paradox + Let's Hangout at SXSW 2025 + Generative AI on Wikipedia

The last time that I attended South by Southwest (SXSW)—Austin’s sprawling festival for tech, film, music, and more—it was 2013, and I was in my mid-twenties. Back then, startups were throwing parties left and right, and you had free admission if you showed that you’d downloaded their new app on your phone. The highlight of the trip was randomly running into Snoop Dogg and convincing him to take a picture with us.

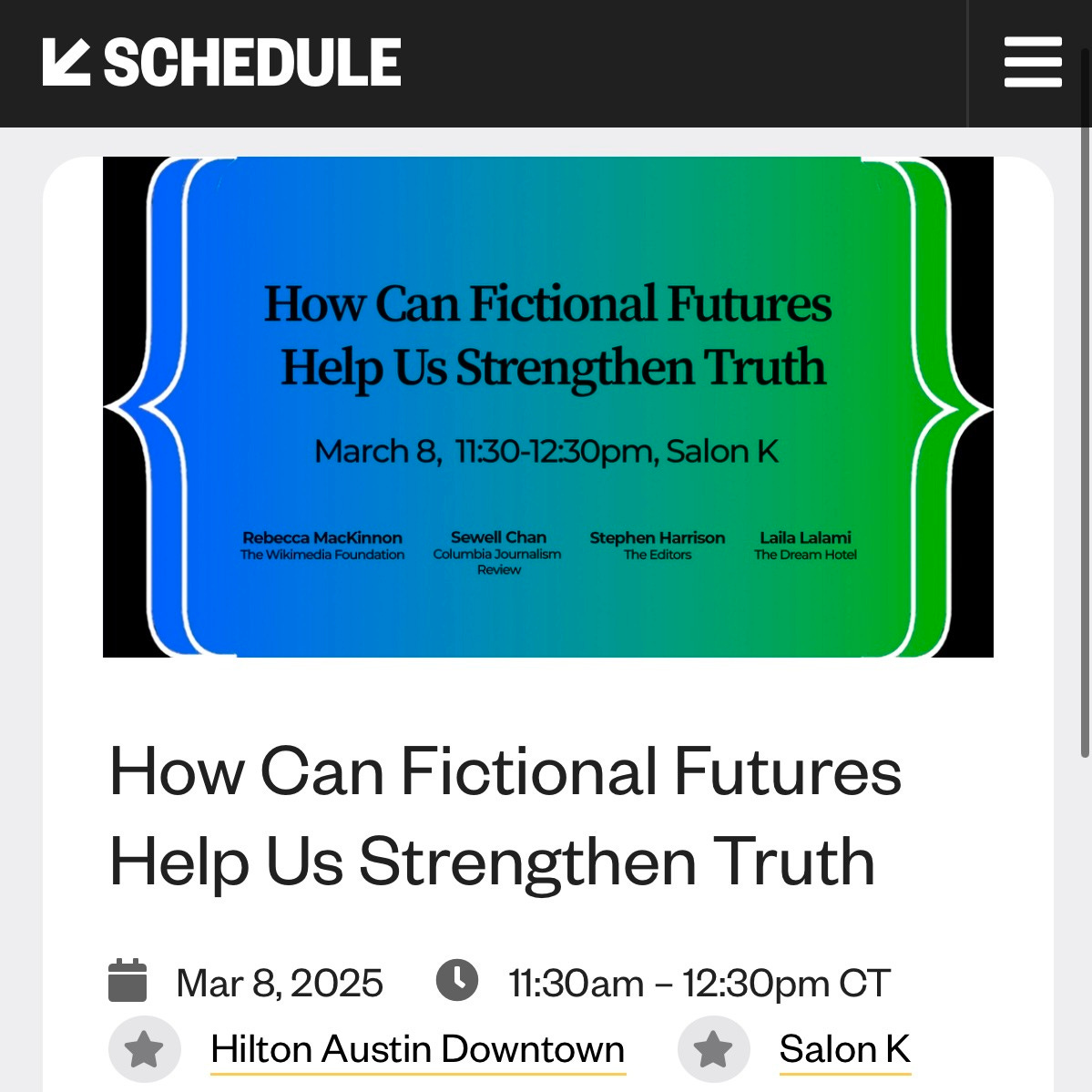

Flash forward to this Saturday, March 8—I’m heading back, but this time as a speaker and the author of The Editors. Our panel is on the surprising ways that fiction can help strengthen truth—one of my favorite paradoxes.

I’m a bit intimidated, to be honest, because the panel includes esteemed novelist Laila Lalami, Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of The Dream Hotel (a chilling new release where even dreams are under surveillance), alongside Rebecca MacKinnon, with Sewell Chan of the Columbia Journalism Review moderating. In other words: I’m the least qualified person in the room—but honored to be there.

Thinking Out Loud Before SXSW

It seems to me—at least on an intuitive level—that there’s a truth in fiction that isn’t captured by straight nonfiction reporting. William Faulkner once said, “The best fiction is far more true than any journalism.” I tend to agree.

On the panel, I might speak a bit from my practical experience as a journalist covering Wikipedia for several years. Many times, I was overwhelmed by the sheer amount of data available on the platform: the number of articles, the thousands of edits on very contentious pages, the hundreds of volunteer editors involved. When I was writing my journalistic articles, I found I was more successful reporting the facts if I forced myself to focus on a specific event. For example, This company tried—and failed—to manipulate Wikipedia last week, or This prolific Wikipedia editor has been banned: Here’s why.

Then again, I always worried that by limiting my scope to that week’s newsworthy event, I wasn’t appropriately communicating the fullness—or you might say, the truth—of Wikipedia.

When it came time to write a book on the subject, I gravitated toward writing it as a novel, and specifically, a suspense novel. It wasn’t an entirely conscious decision, but in retrospect I see two key benefits to writing it as fiction.

(1) Distillation - The real-life English Wikipedia has something like 1,500 power users, and a true, holistic nonfiction account would document each of their contributions. Not only would that lengthy account be impossible for me to write (as a human), but it would also be unreadable (as a human). So for the novel, I focused on four main perspectives: young editor, seasoned editor, journalist, and rulebreaker. In other words, I distilled.

Distillation is a tricky business because you don’t want the characters to be reductive or cliché. A lot of the work as a novelist comes in ensuring the characters are authentic with their own motives and not mere stereotypes or pawns of the plot. And distillation ≠ summary. It must preserve essence; not diminish it. The aim is lightning in a bottle that’s still lightning.

You may have heard the maxim: “In a world of endless information, curation is the key.” There’s a practical, can-do spirit to curating your feeds and collecting reliable sources. I like this principle, but I’ve started to think distillation is the better word. In a world drowning in data, distillation is the key—especially through fiction.

(2) Perspective - Fiction’s second power may be even greater than the first. Fiction can explore viewpoint and the inner lives of characters in a way that isn’t captured by pure data journalism, much less AI reports.

For instance, I can now ask an AI tool to summarize the back-and-forth debate on the talk page of a contentious Wikipedia article. It can give me a bulleted list of the key arguments raised on each side. However, the AI tool cannot tell me about the inner world of the person who is advocating for a certain change. It can’t communicate their thoughts and feelings in the moment. This is the domain of fiction, which provides a simulation of consciousness. As a reader, you can step into the skin of the character and experience their perspective.

Here’s a question: Which version of events is truer—the AI summary of a real Wikipedia debate, or a novel that simulates the human experience of Wikipedia editing? The answer isn’t obvious.

AI can summarize the facts pretty well, particularly by drawing on a dataset like Wikipedia. Fiction, however, can communicate something deeper by immersing us in the characters’ lived experiences. I think that’s what Faulkner was getting at.

***

As you can probably tell, I’m still kicking around these ideas in my head. What else do you think I should say?

And please let me know if you’ll be in Austin for SXSW on March 8. I would love to meet some of my readers in person.

Other things worth sharing

The Balsillie School of International Affairs has launched Balsillie Case Studies, a “repository of evidence-based true stories of technology-related governance dilemmas across various sectors globally.” My case study for the series is titled “Wikipedia’s Governance Challenge: Policies and Guardrails for New Generative AI Technologies.” I’m excited to see how students grapple with this real-world scenario and what recommendations for Wikipedia come from the classroom.

Last month, my book club read Fahrenheit 451. This March, we’re reading The Stranger by Albert Camus. Drop me a note to join.

Have you read The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien? (Great post, btw.)

Love this! Enjoy round two of SXSW!